An Effort to Better Value Baseball Players - Part I

Diving into Wins Above Replacement in my quest to better quantify greatness.

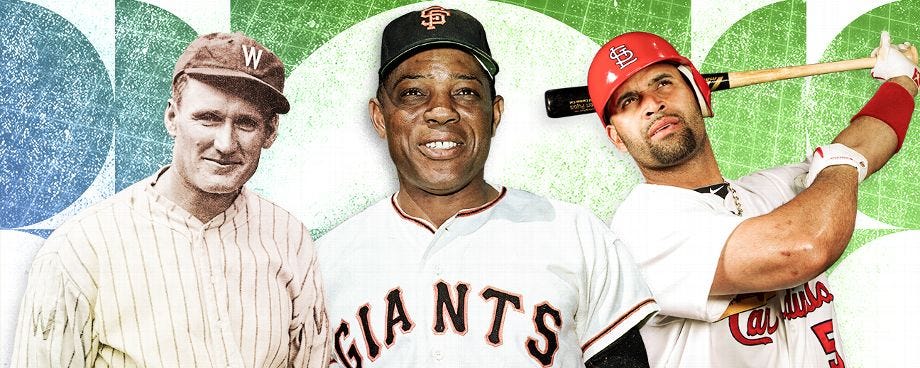

It is the never-ending debate - who are the best of all time? Baseball is inundated with stats, and countless metrics have been developed over time in an effort to identify the best players. In this series of articles, which will run periodically throughout the course of this season, I will look into ways to better quantify the value and ability of baseball players. While it frankly may be impossible to find an exact and perfect metric to adequately value players, both today and across the long history of the sport, even a small improvement is a victory. But honestly, isn’t the debate one of the things that makes baseball, and sports in general, so captivating?

This edition features an investigation into Wins Above Replacement (WAR). MLB.com defines WAR as “[a measure of] a player's value in all facets of the game by deciphering how many more wins he's worth than a replacement-level player at his same position (e.g., a Minor League replacement or a readily available fill-in free agent)”. It is useful because it “quantifies each player's value in terms of a specific numbers of wins. And because WAR factors in a positional adjustment, it is well suited for comparing players who man different defensive positions”.1 A recent article by Neil Paine on Mike Trout (“Mike Trout and the Fragile Pursuit of GOATdom”), on how his unfortunate streak of injuries has hindered his pursuit of becoming one of the (if not THE) greatest to ever do it, led me to think about WAR in a slightly different way. WAR, a counting stat, fails to account for time a player has missed, whether or not it was the fault of his own. Players missed out on opportunities to rack up WAR in the pandemic-shortened 2020 season and during the labor-strikes in 1994 and 1981. Some all-time greats like Ted Williams and Bob Feller left the sport for three years to serve our country in World War II. Prior to 1961, the MLB played a 154-game schedule, as opposed to its 162-game schedule today. A small difference, yes, but over the course of a 20-year career that adds up to 160 games (one full present-day season!). Additionally, it has become increasingly clear from research that when the league was segregated, the talent in the American and National Leagues was not significantly better than that in the Negro Leagues. Negro League players are at a disadvantage from a statistical perspective however, as the Negro League teams played significantly fewer games, often fewer than half the number of games played in the AL and NL. Lastly, while there is something to be said for a player’s ability to stay healthy in regard to their all-time greatness, can we really fault guys like Lou Gehrig, who had to retire and end his consecutive game streak due to ALS? Former Yankee captain Thurman Munson died in a plane crash in the middle of his career, should that take away from our perception of his talent as a baseball player? Is cumulative, career-long WAR really the best measure of greatness?

Can we do WAR better?

What if we looked at Wins Above Replacement as a rate-based stat, rather than a counting stat? How would leaderboards look if we considered WAR on a per-game basis as opposed to a cumulative total? Below are tables of the top 100 position players and pitchers of all time by Wins Above Replacement2, along with whether or not they have been inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame (or will surely be once eligible or would be if not for PED allegations).

It’s no surprise that indisputable all-time greats like Babe Ruth, Barry Bonds, Willie Mays, Roger Clemens and Cy Young top these charts. But now let’s compare these to the top position players and pitchers by Wins Above Replacement per 100 games played.3

Many of the all-time GOAT candidates still land fairly high on the list, but we see a few interesting trends arise. We see the appearance of some Negro League players like Oscar Charleston, Turkey Stearnes, and Bullet Rogan. We see some chronically injured players show up, like Jacob deGrom, Mike Trout and Stephen Strasburg (leading us to ponder what could have been if these phenoms had just managed to stay healthy). And we also get a glimpse into some younger current players who may be destined for all-time-great status, like Aaron Judge and Gerrit Cole. I find it quite fascinating to compare these two lists.

What does the Hall of Fame think?

Which viewpoint has mattered more in the eyes of the Baseball Writers of America and special committee members who vote for the Hall of Fame? Unsurprisingly, it is the standard WAR calculation. I found a correlation coefficient of 0.64 between a pitcher’s WAR and Hall of Fame status, compared to a 0.34 correlation between their WAR/100G and Hall of Fame status. For position players, the difference was slightly closer at 0.68 and 0.45, respectively. So, we know what the voters value, but are they valuing what matters? That is what is up for debate. What truly matters in valuing greatness is ultimately what the fans think matters, so you tell me, drop your vote below!

Today’s players

Let’s close this out by looking at the top active players by WAR, along with their WAR/100 games. Which one looks like a better metric to judge the current players we watch on the field now?

As I said, we will be diving more into this topic of re-defining player value throughout the 2024 season, but for now, the question still lingers…

Wins Above Replacement (WAR) | Glossary | MLB.com

Using FanGraphs WAR calculation

I used 100 games instead of per-game as it is much easier to comprehend, as the per-game basis yields a pretty small number.

Both strike me as valuable in understanding the value of careers. However, I recall years back Bill James looked at two metrics in his Historical Baseball Abstract - Peak Value and Career Value. In other words, who was the best at their peak (even if their career was unexpectedly short) and who was the best over the course of their career?

Career Value seems adequately covered by WAR, either total or per-game...but Peak Value strikes me as something very interesting and different to stare at. Much of this gap in appreciating Peak Value today feels driven in part by baseball's early counting stats obsession, where talent was viewed myopically as simply the accumulation of raw stats.

Talent is a function of both level and duration. James' Peak Value insight - like so many great insights - is not limited to baseball. For example, you could use that talent framework anywhere - the business world, music, TV shows, books, technology etc. Some elements of our culture are enormously impactful, even if they only last a few years, while others are appreciated for their longevity.

Anywhere achievement can be witnessed and assessed, understanding the difference between Peak Value and Career value - both of which are valuable - creates deeper understanding. Peak greatness - even if for short periods - is an insight I feel we are missing today that James tried to capture. Perhaps something to focus on again.